As the bright displays of Vivid Sydney cast a visual story on Customs House we gathered as part of a Finding Nature event exploring the implications for climate action when 40% of humanity goes to vote. During this event Bob Carr, the longest standing Premier of New South Wales and Australia’s former Foreign Minister shared insightful nuggets from his career and the zero-sum game playing of geopolitics. The evening was not only enlightening but also featured a fun segment of Bob Bingo, adding a lighter note and playfulness to the seriousness of the event.

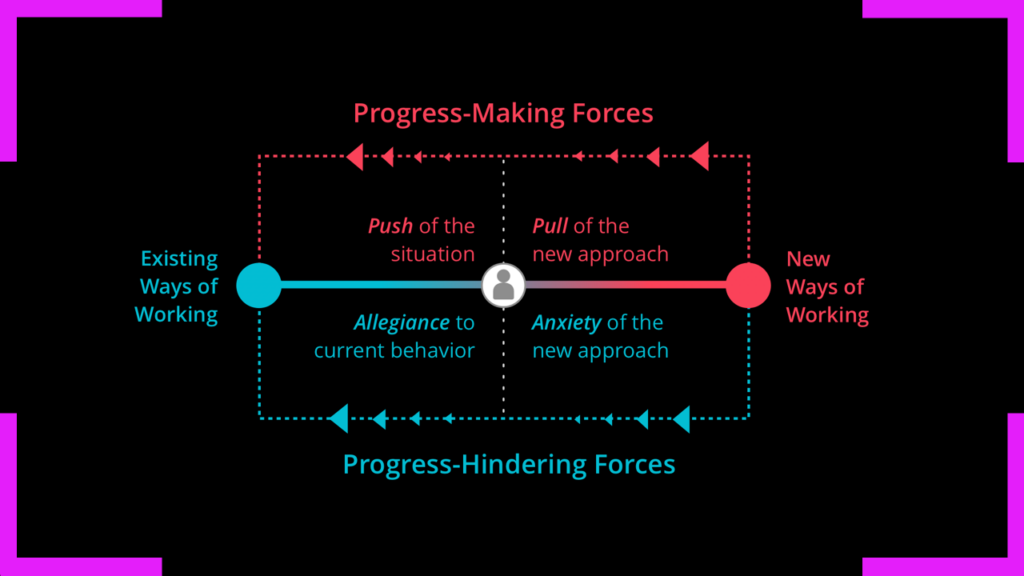

What struck me most, however, was the pervasive mindset of optimising for avoidance of the worst possible outcomes, to the detriment of striving for the best. This lack of moral courage and the narrowness of the Overton windows that frame acceptable policy were evident in the discussion and stories he shared.

Understanding Hegemonic Masculinity

Reflecting on some of my academic journey, a large portion of my first year at university was devoted to understanding the dynamics of hegemonic masculinity. Engaging in literature on the topic and also doing my own ethnographic research with people who would be considered to be wealthy and powerful in Australian society. Sociologist Raewyn Connell’s extensive works, along with “Ruling Class Men: Money, Sex, Power” by Mike Donaldson and Scott Poynting, provided a profound understanding of how cultural contexts cultivate ruthlessness, emotional detachment, and perpetuate broader social dysfunction. These expressions of inherited privilege shape our world in their likeness.

Hegemonic masculinity to the dominant social position of men, and the cultural norms and values that support and legitimise this dominance. This concept helps explain why certain behaviors and policies prevail, even when they are detrimental to the collective good. The traits associated with hegemonic masculinity—competitiveness, aggression, emotional detachment, and a focus on power—often drive policy-making and leadership styles that prioritise short-term gains and risk aversion over long-term planning and cooperation. I’d argue that Bob and many of his counterparts are subject to this. None of use are beyond the influence of the dominant forces that shape our perception of the world, ourselves and the world we live in.

But how does this more directly influence policy?

Short-termism and Risk Aversion: The emphasis on competitiveness and immediate results, characteristic of hegemonic masculinity, fosters a short-term focus in policy-making. Leaders driven by these norms may avoid taking bold, long-term actions due to fear of vulnerability or appearing weak, thus perpetuating a cycle of risk aversion.

Zero-Sum Thinking: Policies shaped by hegemonic masculinity often reflect zero-sum thinking, where one party’s gain is perceived as another’s loss. This mindset can hinder collaborative efforts and international cooperation, as nations and political entities prioritise their own interests over collective well-being.

Perpetuation of Inequities: The cultural contexts that cultivate ruthlessness and emotional detachment also perpetuate broader social dysfunctions, such as economic inequality and social injustice. These inequities are often maintained by policies that prioritise the interests of the ruling class, reinforcing the status quo.

Bold Policies for Positive Change

Bob Carr grew up in my local electorate of Maroubra on Gadigal Country in Sydney Australia and during his early political career nature conservation was a big priority. Building on his first appointment in the New South Wales Legislative Assembly in 1984 as Minister for Planning and the Environment. At least for me he was a symbol of positive political change during my teens. Now I wouldn’t say his policies were bold and morally courageous. Particularly in the sense of what I believe we need now. At best they were simply incremental change representative of the dominant trend in any progressive political arena.

During the conversation on the evening Bob also drew attention to the harsh realities of a potential second Trump term in the US and the terrifying implications of policies like the deportation of 20 million people. While these are bold and concerning, I believe we can advocate for equally bold policies that drive positive change.

My reflection is that maybe the recipe to all this lies in countering the force of hegemonic masculinity and the importance of feminine leadership?

Embracing the values often associated with the feminine does not mean attributing these qualities solely to women but recognising the importance of attributes such as empathy, cooperation, and long-term thinking in leadership and policy-making.

Sophie Howe, Wales’ Future Generations Commissioner, exemplifies this shift. Her role involved ensuring that public bodies consider the long-term impact of their decisions on future generations, embodying a proactive and inclusive approach to policy-making. And she’s been continuing to catalyse this world globally over the last few years. Work that demonstrates the power of feminine leadership in cultivating what might be more aligned to indigenous thinking and the seventh generations principle.

Seventh Generation Principle is an Indigenous Concept, to think of the 7th generation coming after you in your words, work and actions, and to remember the seventh generation who came before you.

The Prospect of a Future Generations Commission

One question that lingered with me after the event given I didn’t get to ask it in the final Q&A was about the prospect of establishing a Future Generations Commission in Australia, similar to the one in Wales. This is something I’ve done a decent amount of thinking on and last year with a few collaborators proposed something similar in a consultation submission for Australia’s Draft National Science and Research Priorities. So given the current Overton window leading into the 2025 federal election in Australia and the Duty of Care Bill shifting political discourse, how might this change the game?

In Wales, the Future Generations Commissioner works to ensure that public bodies consider the long-term impact of their decisions on future generations. This role embodies a proactive approach to policy-making that transcends the short-termism and incrementalism we often seen in politics. By prioritising the well-being of future generations, Wales took significant steps towards sustainable development and intergenerational justice.

I believe doing something similar in Australia could be transformative. It would be the type of bold and morally courageous policy we need. And given the environment was a big theme for voters in the last federal election in Australia, could be a decisive position to take. Having a dedicated federal government function like this would institutionalise the consideration of long-term impacts in policy decisions, helping to shift the focus from merely avoiding immediate risks to actively optimising for the best possible outcomes. Such a commission could advocate for policies that address climate change, social infrastructure to support adaption, help address economic inequality, and catalyse more social cohesion with a future-oriented perspective.

It could fundamentally alter the dynamics of our policy-making processes. But it would not be without challenges. It would require a significant cultural and political shift, with buy-in from various stakeholders. Though I would say the potential benefits far outweigh the difficulties. I’m sure you’d agree that by fostering a long-term perspective in policy-making, we can begin to address some of the root causes of the challenges we face and create a more resilient and prosperous society.